Interrogating Inaccuracies: Hate Crime Data and APIDA Communities.

By Alisha Keig and Dr. Faith R. Kares

Anti-Asian violence is rarely categorized as a hate crime by law enforcement. In fact, it is worth noting that the very process of determining what constitutes a hate crime is deeply flawed, revealing how various legal institutions play crucial roles in reinforcing identity hierarchies and dismissing the intersectionality that shapes people’s lives. The FBI has the most comprehensive set of hate crime data; however, there are major issues within the data collection and reporting processes. Most glaringly, that data is given to the Bureau on a voluntary basis. Only 14 percent of the over 15,000 agencies that participated in the FBI’s hate crimes program actively reported incidents to the FBI in 2019. Forty percent of states also don’t require hate crime data collection or don’t have hate crime laws in place. To top it off, there is no national, standardized definition of what a hate crime is, creating inconsistencies from state to state and agency to agency. Statistician Mona Chalabi, in a recent instagram post, underscores these challenges posed by data collection and analysis practices: “Hate crime data pushes victims to choose between their gender or their race when they make reports...I don’t know what percentage of victims were women *and* Asian *and* sex workers...All I know is that headlines about ‘Asian fears’ miss the point entirely…[and] deflect attention away from the white supremacy that exists every single day in the US…” Such inaccuracies in defining, collecting, and reporting intersectional data only serve the oppressor and continue to erase, relegate, and ignore APIDA communities. Indeed, if Asian women themselves are either invisible or dysfunctional then how can anyone actually be held responsible for any violence done unto them?

Chalabi also asserts that violence against sex workers is clearly normalized by the fact that no data is available. According to WHO, sex workers continue to face violence because of stigmatization and discrimination, and all countries should work to decriminalization sex work.

The Atlanta murders is a tragic case in point: news outlets, law enforcement, and our president refused to directly name the racism and misogyny undergirding the attack and the deliberate targeting of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Desi American (APIDA) women. Investigators deflected and made excuses for the behavior of the assailant, shielding his whiteness, his maleness and his heterosexuality. This is a current example of a longstanding American tradition of white sexual imperialism which began with U.S. servicemen soliciting sex workers during the Phillipine-American War, World War II, and the Vietnam War. The bodies of Asian women were and are treated as objects: hypersexualized, exoticized, and perceived as sexually permissive. The National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) reports 41-61 percent of Asian women report experiencing physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner during their lifetime which is higher than any other ethnic group proving that these stereotypes are dehumanizing and dangerous.

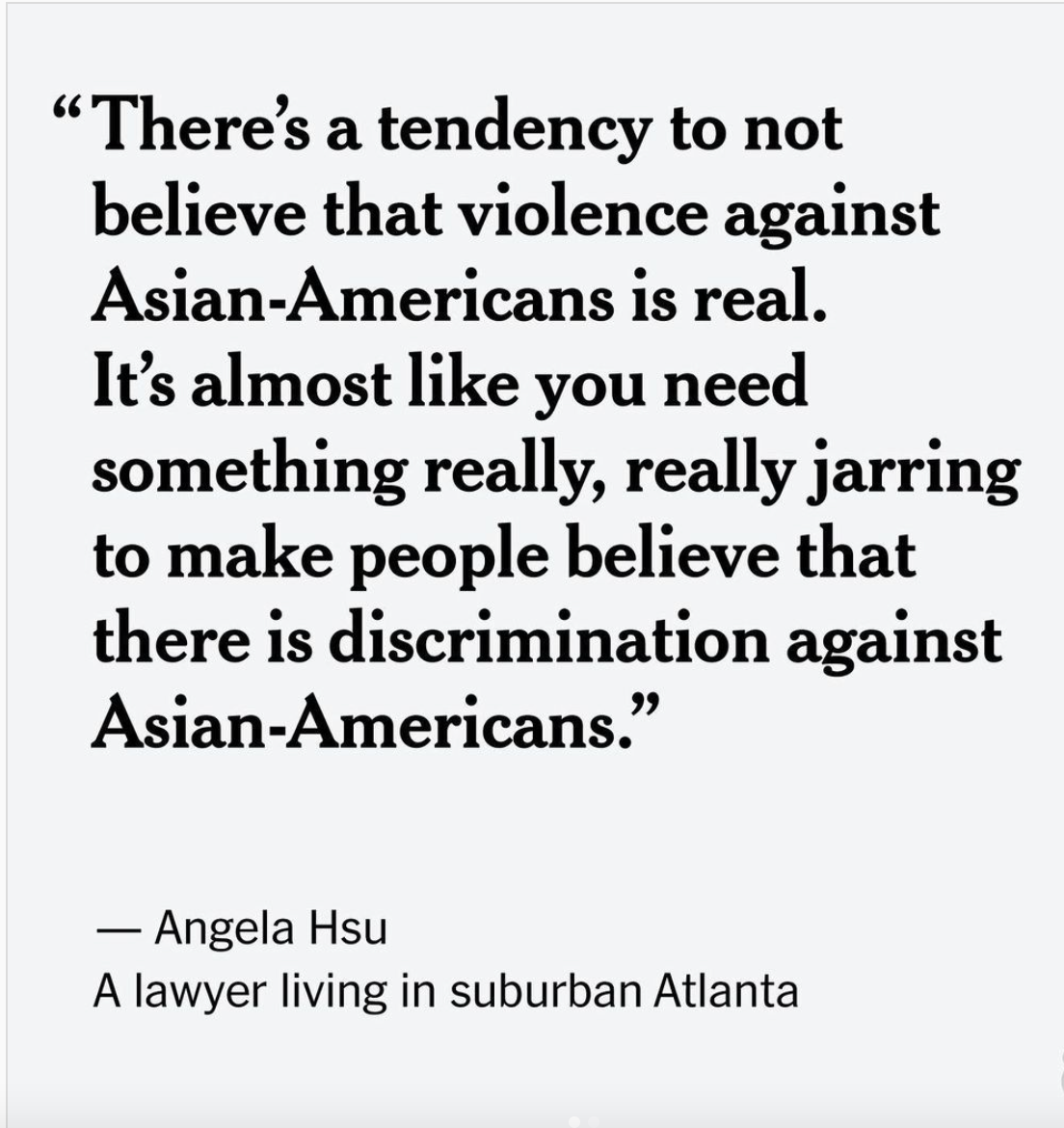

The failure to recognize anti-Asian violence as hate crimes, and the failure to acknowledge and address the persistent objectification of Asian women, dismisses collective trauma and pain. Even if legal authorities and public officials refuse to name anti-Asian violence as a hate crime, Asian communities still experience the violence as a form of domestic terrorism. Such erasure contributes to the invisibility of a community that grapples with tropes rendering them deferential, subservient, and a model minority. Indeed, mainstream media and law enforcement are institutional entities that continue to misrepresent APIDA communities as any number of stereotypical tropes, from “forever foreigners’ who never truly belong in the U.S.” to the “model minority’ that is high-achieving but submissive.” This misrepresentation does not allow for the full range of human experiences in APIDA communities but points to a broader history of naming and labeling non-white groups as Other in order to maintain the current system of white supremacy.

2. Quote taken directly from the National Network to End Domestic Violence. You can read more about how race and ethnicity interact with one another here.