APIDA Complexities: Learning, Unlearning, Relearning

By Dr. DeLa Dos & Alisha Keig

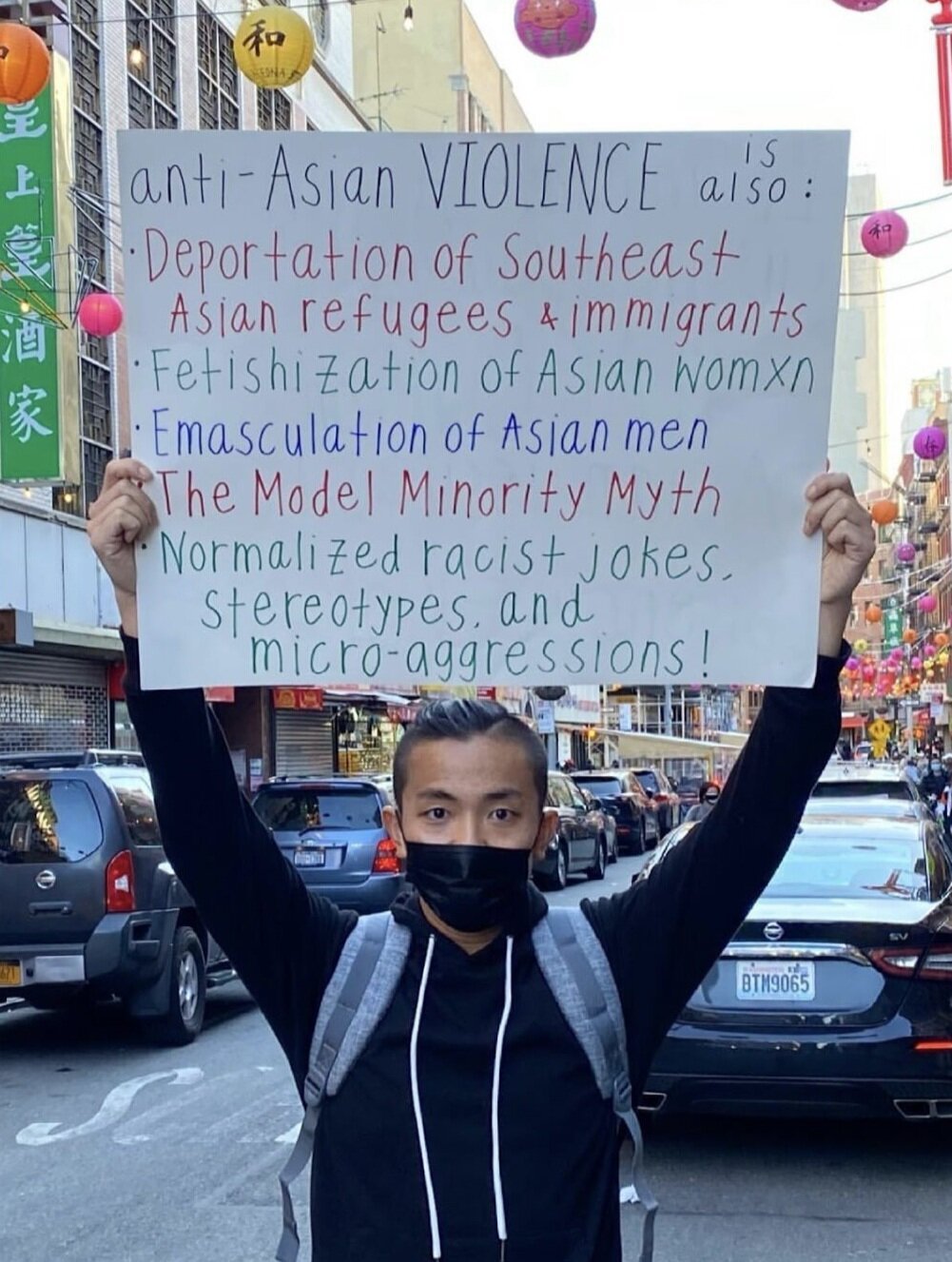

Domestic (to the United States) and global APIDA communities are complex and diasporic. In order to dismantle anti-Asian violence, we must start by disaggregating and differentiating Asian identities, experiences, and cultures that typically get lumped together and create dangerous monoliths. The mythology of the model minority is one of those monoliths. The model minority myth asserts that the “Asian community” is high achieving and successful, positioning them as an exemplar for other BIPOC to emulate. This trope is weaponized to

drive a wedge between racial and ethnic groups to prevent solidarity,

hide the racism encountered by APIDA communities, and

erase the diverse lived experiences of individuals within APIDA communities.

This piece will examine these trends by exploring some of the complexities of APIDA identities and communities in the context of intersectionality.

As APIDA is not an acronym that is universally known, it is often met with both curiosity and critique. It attempts to offer an umbrella label, identity, and community for a large group of people: Asian Pacific Islander Desi American people. It builds on a long string of previous labels, and it includes aspects of oppression and erasure as well as empowerment and resistance. For some, it is a sensitive subject. For some, it is a subject of no value. For some, it is a point of contention. For some, it is a point of pride. While there are nigh endless potential responses and no singular authority on its meaning, at its core, APIDA is a complex marker within the larger social construct of race. As with all socially constructed identities, it is important to consider the identity in the context of the society in which it was constructed. For APIDA, this means the United States.

Complexities of APIDA

APIDA has many predecessors—API (Asian Pacific Islander), AA (Asian American), and Asian. As the language evolved, it revealed more of the complexity of the community (and communities) it is meant to represent. These labels have shifted with various social trends and attitudes, which often included aspirations of increased inclusion. Asian and Asian American emerged in response to longstanding practices of using various problematic labels such as oriental and Chinese. Race and ethnicity labels were, and continue to be, used in informal and official capacities by individuals and systems. The included screenshot is from a website from the United States Census that maps the language used to categorize race and ethnicity from 1790–2010.

One of the reasons APIDA is complex is that it is meant to encompass such a vast breadth of identities. This effort is motivated by a desire for convenience in upholding a system of racial categorization (in the US) that was not designed to recognize the existence of these people, let alone honor them. In 1790, the census used three categories for race: slaves; free white females and males; and all other free persons. Slavery is at the core of the social construction of race in the US. This focus included a reduction of the vastness of human experience and identity to the distinction between slave and free person; even still, not all free persons were created equal.

Fast forward to 2019, the United States Census estimated Asians (alone, i.e., monoracial/not multiracial) to be 5.9% of the nation’s population; for Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (alone), the estimate was 0.2%. Combined under an APIDA identity, this group is just over 6% of the US population. Compare that with world population estimates, Asian Pacific Islander and Desi nations are over 55% of the global population in 2020. The calculation of this estimation requires overlaying US concepts onto geopolitical categories. It includes Southern, Eastern, and South-Eastern subregions of Asia while excluding the Central and Western subregions, as these are often included in other socially constructed markers such as Middle Eastern North African (MENA) and SouthWest Asian North African (SWANA). Pacific Islanders are identified by including the Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia subregions of Oceania while excluding Australia & New Zealand; this results in approximately 0.1% of the world’s population. The impact of these groups being included in the same umbrella label as groups that are 55% of the world’s population should not be missed; the experiences, voices, perspectives, and existence of Pacific Islanders are regularly erased. The following chart summarizes these numbers.

(data from the United States Census & worldometer.info)

While the complexity of trying to lump over half the world into one racial category may lead some to recognize the futility of such efforts, a combination of various systems of values and beliefs, like ethnocentrism, white supremacy culture, and racism, results in this as an accepted, common practice. After generations of this practice impacting generations of immigrants, residents, and citizens in the US who could trace their heritage to Asian and Pacific Islander nations and cultures, the socially constructed identity that was used to de facto erase the nuance and diversity of the APIDA community was reclaimed. Individuals and communities began embracing the politicized nature of an Asian American identity. And while this energy led to the founding of the first Asian Asian American studies programs in the late 1960s, systemic and structural barriers still limit the prevalence and momentum of these efforts (e.g., After 50 years, Asian American studies programs can still be hard to find).

Through an iterative process of existence, response, review, and empowerment, the language shifted and expanded. Pacific Islander was lifted up in response to the omission of these communities in conceptualizations and considerations of Asian identity. Similarly, Desi was lifted up in response to the omission of South Asian communities. Along with these changes come challenges. There can be confusion about differentiating South East Asian communities and Pacific Islander Communities, both of which are often overlooked within and beyond APIDA communities. The use of Desi includes the limitation that not all South Asian people identify as such. These are some of the inherent problems with attempting to set one racial category for over half the world’s population. Still, when that group is just six percent of the population of a nation that has racism interwoven throughout its history, structures, and operations, there can be value in pursuing connection, community, and coalition.

Complexities of Intersectionality & APIDA Identities

Categorization is a natural part of human brain function. It is an essential part of how we process information. It is inextricably linked to how we learn. While categorization has a number of essential functions, it also comes with a number of limitations. No community is a monolith; this is particularly true when it comes to the APIDA community—again, +55% of the world’s population. Two critical, and interconnected, concepts can help combat the societal propensity of portraying and upholding a monolithic view of the APIDA community: disaggregation and intersectionality.

Data analysis and manipulation illustrate the value of disaggregation. The following example uses data from reports from the Center for American Progress on 10 Asian American (note, not Pacific Islander) communities. The reports include information on population numbers, states of residence, educational attainment, income & poverty, civic participation, language diversity, immigration and nativity, labor force, and health insurance from 2013. Each report also includes details about US population overall as well as the aggregated Asian American population. Reviewing these reports provides ample evidence of the limitations of only using aggregated data.

(reports from CAP, 2015 using 2013 Census projections)

Using educational attainment as an example, the percentage of Asian Americans overall that have less than a high school degree is comparable to the percentage of the US population overall (14.0% and 13.4% respectively). In the category of bachelors or higher, Asian Americans overall have a higher percentage of educational attainment in comparison to the US population overall (49% and 29.6% respectively). When disaggregating the Asian American data by community, however, we see huge disparities within the group. For example, for the category bachelors or higher, the average attainment for Indian Americans is 72% while the average attainment for Laotian Americans is 59 percentage points less. Additional details are displayed in the following chart.

The same within-group disparities can be extended to other economic and social indicators. For example, this fact sheet, created by the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (NAPAWF), shows that once disaggregated, APIDA women experience extreme wage disparities within race/ethnicity. For every dollar earned by a White man, Taiwanese, Indian, and Malaysian women earned $1.21; however, Cambodian, Hmong, Samoan, and Tongan women earned just 60 cents.

The recent murders in Atlanta also speak to the intersectional oppression that APIDA women experience. APIDA women are targets of fetishization and coveted because of dehumanizing and stereotypical portrayals of their bodies as locales of pleasure for men (re: heterosexual men). Meanwhile, these women are denigrated and systematically erased. In the early 20th century, for example, Filipino men were recruited from the Philippines for their labor. However, the US government did not want Filipinos to reproduce in America so they barred Filipina women from immigrating. Filipino men were also forbidden from having any relations with white women. These types of restrictive immigration policies have paved the way for multiple persistent stereotypes including APIDA men being cast as emasculated and effeminate as well as desexualized while APIDA women are often fetishized and hypersexualized (for further reading, see Bonus 2000, Choy 2003, Okihiro 1994, Wu 2002).

This piece scratches the proverbial surface of the complexities related to APIDA identity. Numbers, exposure, and social norms are three of the seemingly countless factors that complicate how individuals and groups in the US recognize, understand, and respond to APIDA identities. Still, all of these considerations are framed in the context of white supremacy culture, as racism is endemic to the United States and a threat to public health. This is evident as Black and Brown communities are regularly shown to be disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. A report from the Asian American Research Center on Health documented how the mortality rate for APIDA members of the San Francisco community was the highest of all race and ethnic groups. Additionally, vaccination rates for Black communities lag far behind other groups, though not for the reasons always presented.

And, since activating as a team to create this series, the murders of Black bodies and the extreme violence against APIDA communities relentlessly continues. With this in mind, our Royal Team remains steadfast in our commitment to combating systemic oppression in all its forms.